ZZAZZ's Fools2019, Pwnage 3

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes.

<Parzival> according to the achievements PK3 is encryption (again) and 4 is to hack the server (again)

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

<meep> inb4 the crypto challenge is a weak RSA implementation on gameboy and you have to find the weakness and forge a signature

No not that much although next year…

The task

The task is the usual thing: we have a blob of encoded data, and must decipher it. Bruteforcing verification will be plain impossible, as the blob is fairly large (512 bytes), and the verification function is… interpreting that blob as map data. No known-plaintext attack here (although in retrospect maybe a few bytes of plaintext could have been deduced, but I doubt that would have helped much).

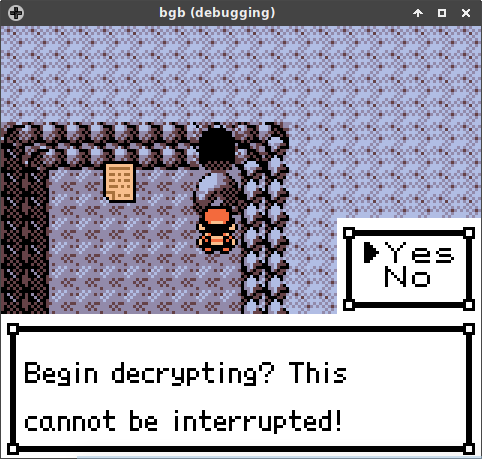

So then what’s the task? Well, we simply need to decipher the blob. What’s special is, the deciphering algorithm is provided, and can be ran as easily as by heading towards a rock and talking to it. What’s the catch then? The problem is NP-hard?

Absolutely not! It’s just that, from a rough measurement, it would take somewhere in the thousands of years. Yipes.

<ISSOtm> By the way, apparently I have found the exploit

<pfero> It’s called a time machine

(This is your friendly reminder that the event lasted 7 days. Also <TheZZAZZGlitch> it has a weakness that reduces the decryption/bruteforce time to a couple minutes on a good machine

, so, yeah.)

*headscratching intensifies*

So! Where to we start? Well first, we need to find the code. The simplest way is to accept our fate and dive right in!

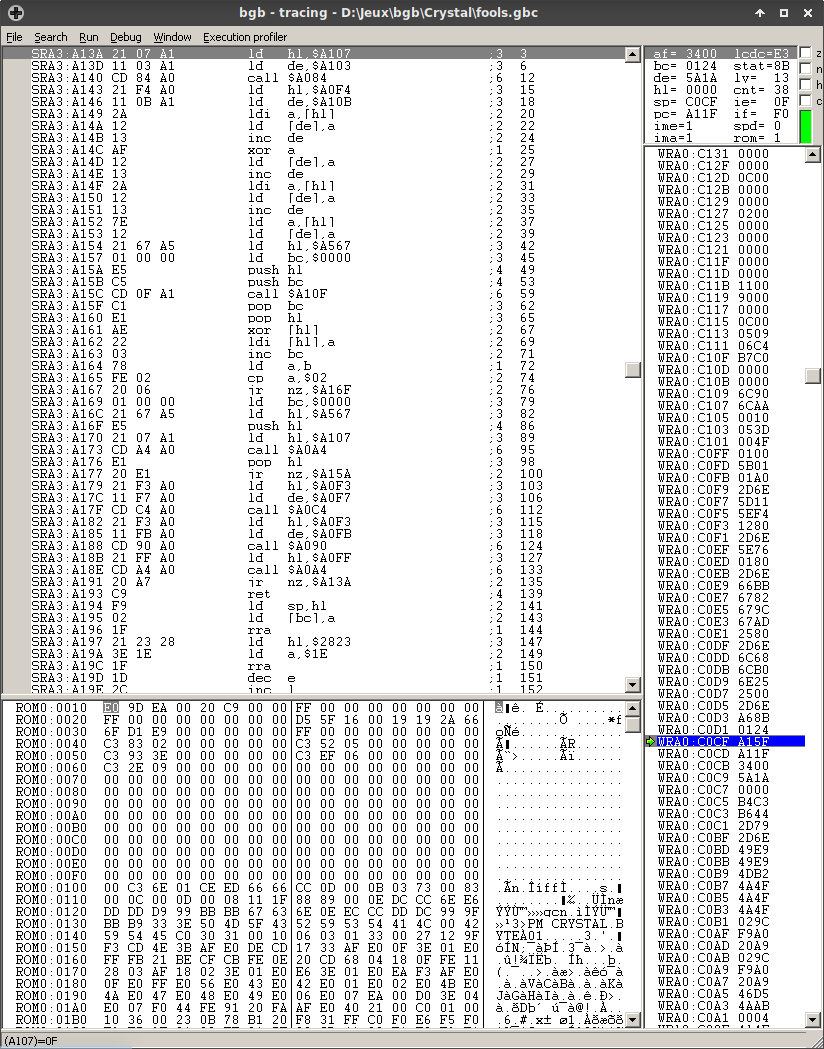

Okay. If we break to the debugger and step out of the VBlank handler, we quickly stumble upon the following function:

That’s… annoyingly cryptic. Luckily some of the functions can be worked out and the ASM can be transliterated to this (very ugly) C. But this is still pretty bad. I could do optimizations and all that jazz by hand, but I wondered if de-obfuscating this and running it on beefier hardware would be enough. Cue gcc -g -Wall -Wextra -O3 -o bruter bruter.c and an eager ./bruter.

This certainly did help, as the ETA dropped to a measly 42 years and a half. But we needed to go deeper, which would probably require reasoning on the algorithm—but this is still quite obtuse, maybe it could be simplified somehow? That I could do by hand, but compilers like GCC tend to be designed to do that in my stead, so why bother?

objdump bruter --disassemble=main -M intel --no-show-raw-insn (snipped to the main loop for your convenience, and without the printf)111d: mov r10d,0x7ffffb0a

1123: mov r9d,0x5d0b1c11

1129: mov edi,r9d ; <------------------+

112c: mov ecx,r9d ; |

112f: mov eax,r9d ; |

1132: xor edx,edx ; |

1134: shr ecx,0x18 ; |

1137: shr edi,0x10 ; |

113a: mov r8d,ecx ; |

113d: shr ax,0x8 ; |

1141: movzx edi,dil ; |

1145: mov ecx,0x1b080733 ; |

114a: nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]; |

1150: shr ax,1 ; <------------------+ |

1153: mov rsi,rdx ; | |

1156: add edx,0x1 ; | |

1159: imul eax,edi ; | |

115c: and esi,0x1ff ; | |

1162: and dx,0x1ff ; | |

1167: add eax,r8d ; | |

116a: xor BYTE PTR [rsp+rsi*1],al; | |

116d: sub ecx,0x1 ; | |

1170: jne 1150 <main+0x90> ; -------+ |

1172: imul r9d,r9d,0x35e79125 ; |

1179: add r9d,0x56596b10 ; |

1180: sub r10d,0x1 ; |

1184: jne 1129 <main+0x69> ; ----------+

If you’re not familiar with x86 assembly, you might be staring at this wall of text confused, which is understandable, but bear with me for a second. Each jne instruction essentially denotes a loop, so we know the inner loop is from 1150 to 1170 inclusive. shr stands for SHift Right, imul for Integer MULtiplication, and add for… something, subtraction maybe?

The most important part is noticing that the addition loop (the one involving a0b8) is actually a multiplication operation! (Bravo, GCC!) A lot of the variables have also been removed, there’s basically two at the top (the two mov r?d,0x???????? instructions), the rest have mostly been absorbed into the program as constants. Good, good, good! It’s now possible to write a new C program based on this:

uint8_t buffer; // Initialization snipped

uint32_t nb_iters = 0x7ffffb0a;

uint32_t outer_lcg = 0x5d0b1c11;

do while;

Much more readable, isn’t it? Now we can start dissecting this.

All roads lead to Rome

This code is slow. Too slow, we know that; but how can we optimize it? The outer loop is run a ridiculous amount of times, and the inner loop is also run too much to be reasonable. We need to either trivialize the inner loop so we can afford to run the outer loop ~2 billion times, or to reduce the amount of iterations of the outer loop. Thus, we need to reason on how the algorithms works, the gist of which is that the buffer is XOR’d with the output of several LCGs - a few billion times, actually.

You may have noticed this acronym in the code earlier—a Linear Congruential Generator is one of the simplest (pseudo-) random number generators. They are essentially close to random, but still deterministic so this code doesn’t spit out literally random data, which would be pretty useless.

And it’s here that I failed a spot check: the period of the outer LCG is 230. I misread the generator’s constants, and incorrectly thought it to be of full period. Amusingly, I did end up exploiting that vulnerability, albeit indirectly, but I guess all roads do lead to Rome.

Anyways, this left me with the conviction that the outer loop’s number of iterations was incompressible, and that I needed to make the inner loop trivial enough that the algorithm would complete in a reasonable time. I had an idea about the outer LCG only having a great period (lol) due to carefully picked parameters, but the inner LCGs’ params would be completely random! Surely there was a way to attack them based on that!

… That turned out to be a dead end. I was stumped for half a day, thinking about how picking LCG parameters would be quite the pickle.

Then it clicked. All of the inner LCG’s output boils down to what it’s seeded with! The 24 bits taken from the outer LCG! And, since we were taking only 24 bits1 but iterating much more than 224 times, there are bound to be repeats—and repeats cancel eachother! It’s thus possible to trivialize the outer loop by only making it collect data about which “inner LCGs” to run, and only then to run the “inner LCGs” that need it!

This is the final code. You’ll note it’s still very unoptimized and close to the original wonky code, it’s because I figured the compiler would optimize it anyways and I’d rather modify the code as little as possible to avoid mistakes. You can run the code yourself if you’re interested, by supplying this file. Just keep in mind that you must compile the program like so: gcc -O3 -o bruter bruter.c. It also unnecessarily eats 16 MB of RAM because I didn’t want to bother with a more complex data structure and rather focus on the math/logic shenanigans.

Technically only 23 bits, since the lower bit of the initial seed is discarded.

Luckytyphlosion’s solution

His solution used the intended flaw, which is exploited by “dry running” the outer LCG the first 230 - N times, then running the actual code N times, N being 232 - 0x7ffffb0a. This takes only a handful of seconds, versus my own code running for around 20 minutes.