ZZAZZ's Fools2019—Pwnage 4

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes.

Pwnage Kingdom 4 was easily the hardest out of all Pwnage challenges. This contrasts with last year, where (I think) difficulty peaked at the 3rd challenge.

Nonetheless, it’s an interesting tale to tell, so strap in! I’m going to expect some familiarity with the Game Boy hardware, but don’t worry, you should be able to process this even without knowing all the technical terms I’m going to use.

The task

You conquered every task thrown at you so far.

Here’s your final mission.Reverse-engineer the game saving system.

To prove your understanding of the save mechanics, you need to create a very special save file for me.

Each completed save file contains a blob encoding variables related to your game progression.

The server then decodes it and updates your progress.

To pass the challenge, every byte in the DECODED blob has to be equal to its offset in the data, mod 256.

So, byte on offset $3F should have the value $3F. And on offset $124, the value $124.

There are two exceptions. First, any checksum bytes are excluded from this rule.

Second, the four decoded bytes at offset $1A5 should have special values: XXX,XXX,XXX,XXX1 (DEC).

This is so it’s impossible to upload files created by other users.

Submit this special file to Pwnage Kingdom IV to finish the challenge. Good luck!

Oh boy.

The XXX values were unique to each user, that’s why they’re redacted here.

Begin

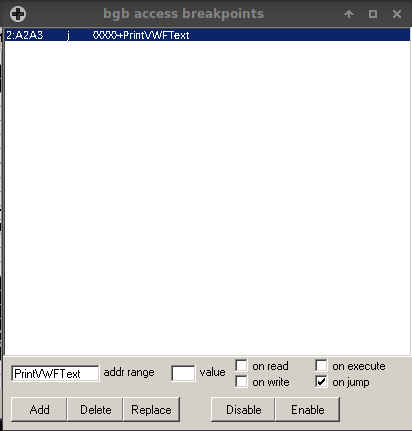

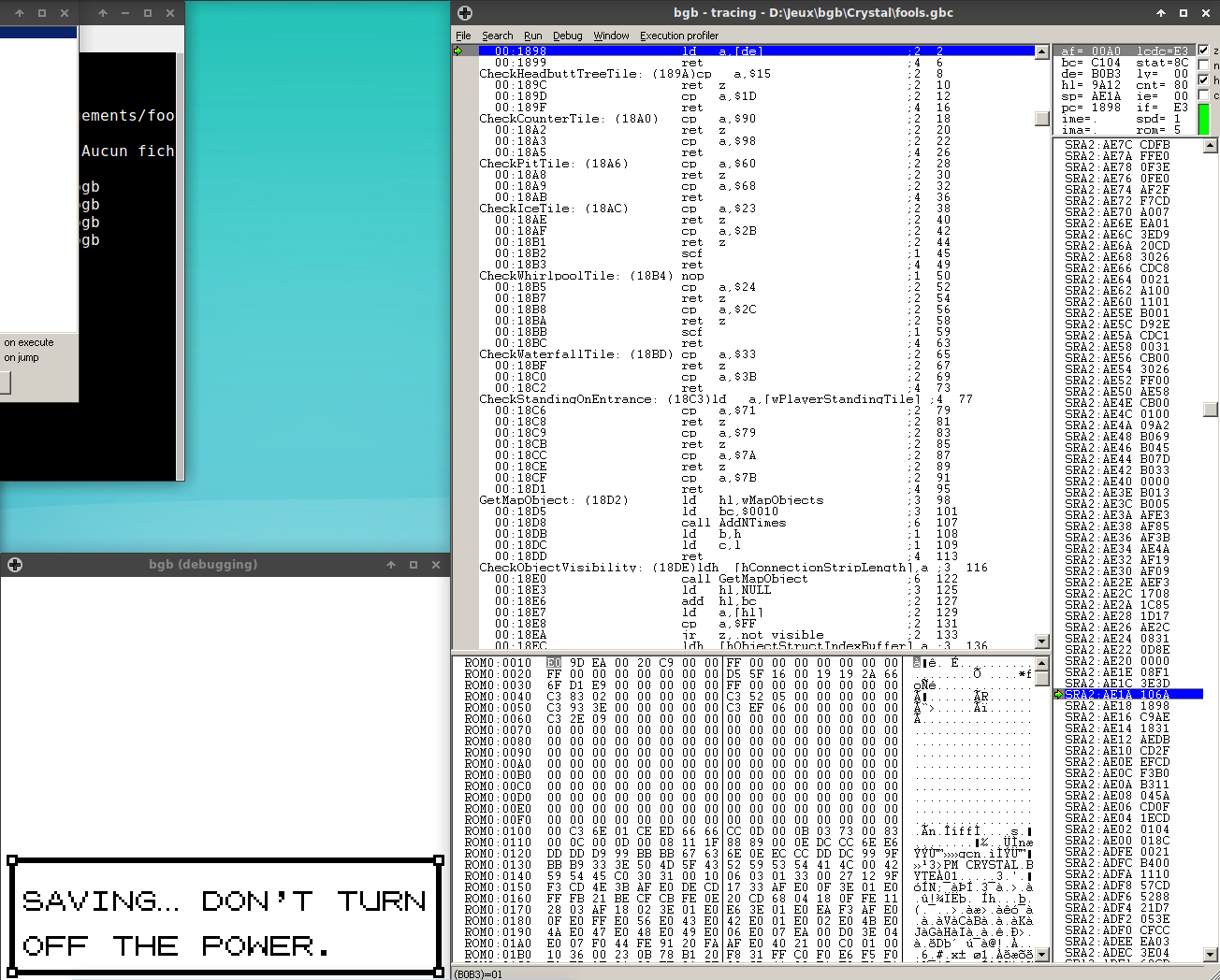

Where do I start? Well, there were a couple of possible entry points, but I had an easy one: I had done prior reversing work on the file and I knew where the text-printing routine was located. (FYI, it’s custom, the base game is unable to print variable-width text, so it’s hijacked to run a custom routine instead). Anyways, the routine I called PrintVWFText is located at 2:A2A3, so I breakpoint’d there and tried saving.

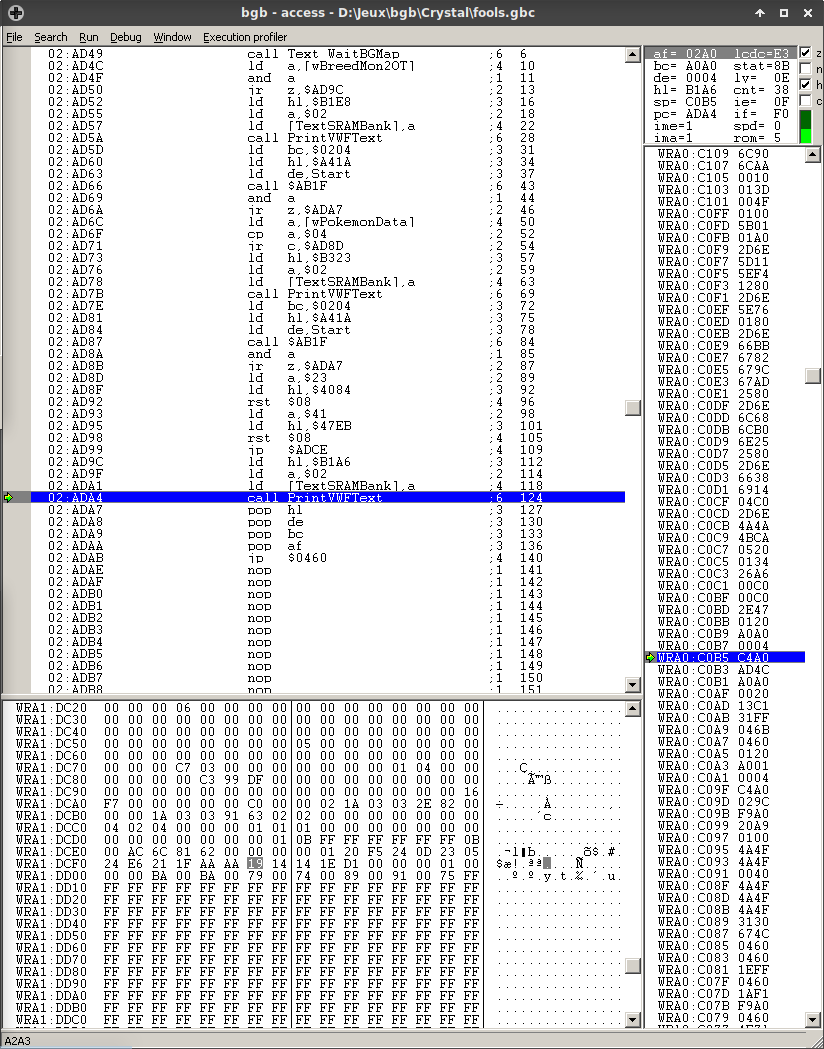

We can see this function is being called from SRAM, ie. from the save file itself. Considering the saving function is hijacked, that’s expected, and a good sign. Let’s step out, and…

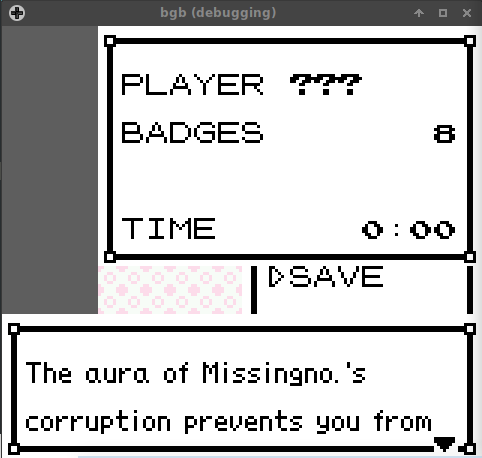

…We need to figure out how to be able to save. (Guess that’ll help figure out where the save code is located, which is a plus, I suppose.) We’ll be jumping into ROM, and the stack only contains ROM afterwards, so it’s no use looking that up. We can repeat the same process with the instruction at 2:AD9C to figure out where the jump is—and if you look closely, it was already in the code viewer, at 2:AD50. Oh well. :P

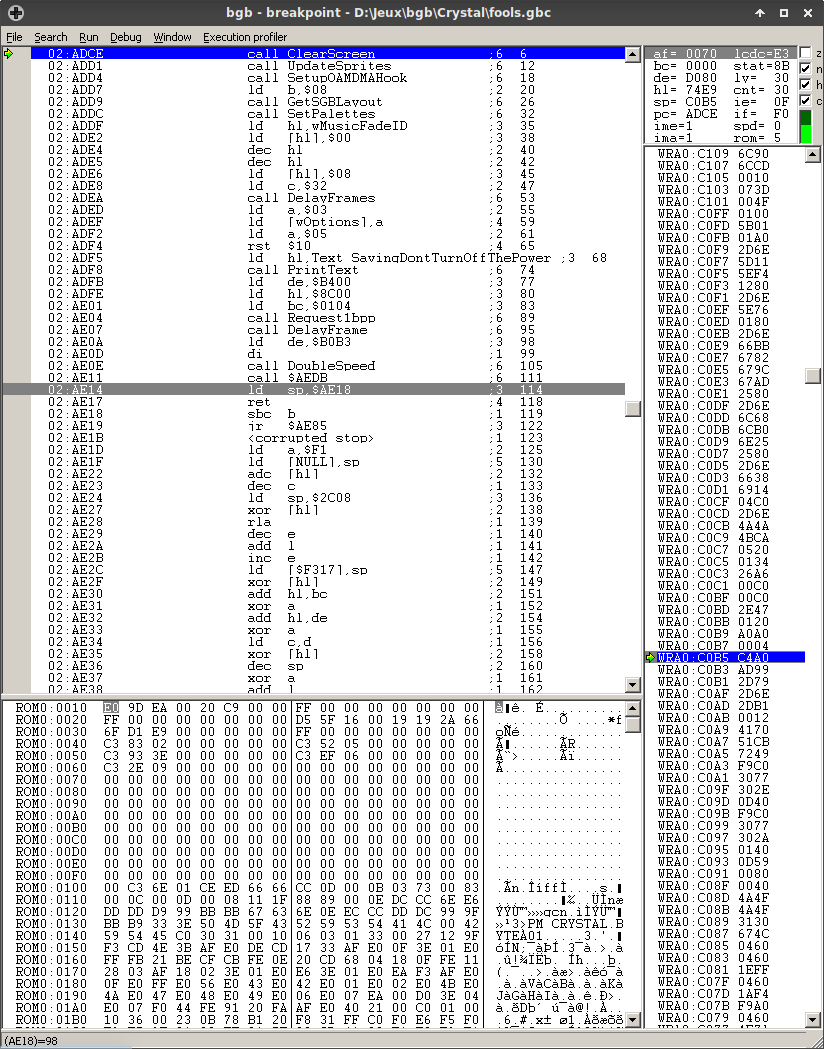

After setting wBreedMon2OT to something non-zero and placing a breakpoint on 2:AD52, I can trace execution to see that none of this code does anything relevant to saving, just displaying the save box. The interesting part is located after the jump to 2:ADCE:

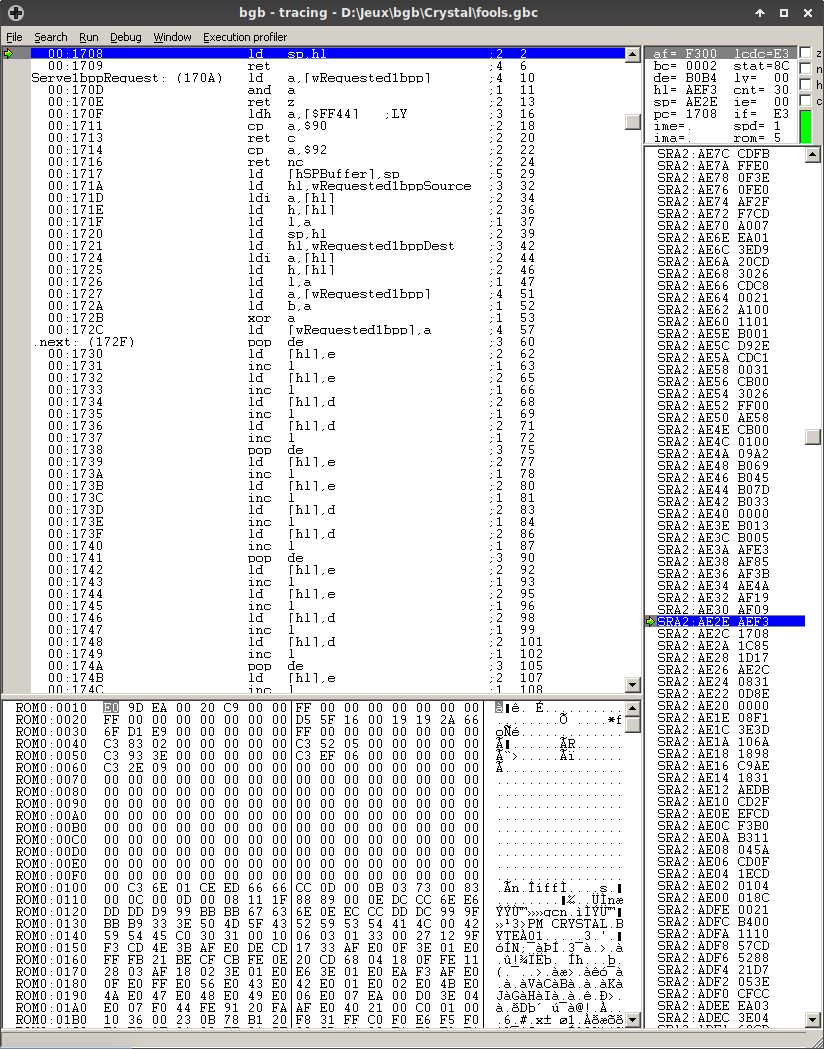

Nothing here is very interesting, there’s some gfx being set up (Request1bpp requests the spinning cursor gfx to be loaded to VRAM, and AEDB writes the cursor to the tilemap), and sp being set to… WAIT WHAT HOLD ON

ISSOtm lost 2 sanity points!"

THAT’S RIGHT BOYS WE DOIN ROP (If you don’t know what that is, you should read this article, as I’ll evoke the term “gadget” which has a fairly specific meaning in this context.)

And don’t worry, things only go downhill from here.

Let’s skip the boring stuff, because debugging ROP is as much fun as counting someone’s hair by picking them apart one by one. I hoped I’d just have to trace the execution and see what opcodes would get executed, but then figure out how that works, but then there’s the gadget at 0:1708…

Okay. After calming down, this is what the function amounts to (content warning: ASM code)

ld a, [de]

inc de

add a, a

pop bc ; ld bc, $0000

ld c, a

pop hl ; ld hl, $AE2C

add hl, bc

ld a, [hli]

ld h, [hl]

ld l, a

ld sp, hl

*sigh* We’re dispatching “calls” depending on what’s at DE. Looks like DE must be pointing at a stream of instructions, and the functions are in a table located at 2:AE2C. Looking at them, we find they also read at DE—that’s right, we have a bytecode interpreter written in ROP!

Technical difficulties, please stand by

After I figured out some of the commands’ functionality and bonked my head against the remaining ones, I called it quits for a couple of days until Darkshadows and Runea offered me to team up, which we did. While they didn’t do much of the detective work, they still had the motivation I had lost to do grunt work, which rekindled mine and allowed us to progress. I believe we couldn’t have made it individually, so thank you very much, guys.

Anyways, we figured out what each “instruction” was—you can find a full dump, albeit lacking names for three commands, generated by this program.

We can notice a pattern that repeats for the first part of the file:

SetReadPtr 0x????

InitChecksumByte 0x??

WriteLong 0x????????

.loop

ReadBufferByte

Scramble

UpdateChecksum

RotateBuffer

Djnz 0x??, .loop

WriteChecksum

RotateBuffer

This basically copies byte from a certain buffer in memory, messes with the bytes written (in a reversible way, mind you), and checksums them. I was initially convinced that the ROP chains, which are in RAM (read: writable memory) would be modified to operate on each byte in the buffer, but turns out that PSYCH! everything operates on the first byte in the buffer, and RotateBuffer rotates the buffer one byte to the left.

The oddball here is this little fellow:

SetReadPtr 0xf84e

.loop3 ; @ 0xb0e2

ReadBufferByte

RotateBuffer

Djnz 0x3, 0xb0e2

which doesn’t have a checksum. Go figure.

Anyways, we still have the final block, which uses command $0D. The locations it reads from are random locations (the game’s RNG state, two clock counters), which I assume are there to mitigate replay attacks and tampering. I’m not sure exactly. But it doesn’t really matter. The buffer is rotated around one last time (at the two Djnz loops, which are there because the bytecode cannot handle looping more than $FF times; also, Djnz 0, X won’t ever jump), checksumming some more, and finally some random stuff is appended, before all of this being copied to the save file.

Phew!

tl;dr wat do

We know what the buffers being read are, their lengths and so on. We can avoid having to re-implement the scrambling and checksum algorithms ourselves by simply modifying the buffers’ contents! ZZAZZ was even kind enough to have bytes mapped in the order they’re read (so the first byte read will need to have value $00, and so on), which is nice. pfero told me that the random part didn’t need to be manipulated, which I suspected but doubted, since I was expecting the worst from ZZAZZ.

Here’s what needs to be done to generate a passing save file: for each line, copy the bytes at the location indicated by the semicolon

000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1f202122232425262728292a2b2c2d2e2f303132333435363738393a3b3c3d3e3f404142434445464748494a4b4c4d4e4f505152535455565758595a5b5c5d5e5f606162636465666768696a6b6c6d6e6f707172737475767778797a7b7c7d7e7f808182838485868788898a8b8c8d8e8f ; fcdf

9192939495969798999a9b9c9d9e9fa0a1a2a3a4 ; fa7a

a6a7a8 ; f84e

a9aaabacadaeafb0b1b2b3b4b5b6b7b8b9babbbcbdbebfc0c1c2c3c4c5c6c7c8c9cacbcccdcecfd0d1d2d3d4d5d6d7d8d9dadbdcdddedfe0e1e2e3e4e5e6e7e8e9eaebecedeeeff0f1f2f3f4f5f6f7f8f9fafbfcfdfeff000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1f202122232425262728292a2b2c2d2e2f303132333435363738393a3b3c3d3e3f40 ; f859

42434445464748494a4b4c4d4e4f505152535455565758595a5b5c5d5e5f606162 ; de41

6465666768696a6b6c6d6e6f707172737475767778797a7b7c7d7e7f808182838485868788898a8b8c8d8e8f909192939495969798999a9b9c9d9e9fa0a1a2a3 ; de99

<YOUR SECRET BYTES HERE> ; 2:a003

Cue appropriate reactions, in the following order

- Pasting bytes: //www.youtube.com/watch?v=EbwhPFDrHUQ (VOLUME WARNING) / //www.youtube.com/watch?v=UvfDISoyvWk

- Bliss from victory message: //www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YCN-a0NsNk

- Lying down on the floor from exhaustion: //www.youtube.com/watch?v=QUAItQmq-LU {: .text-left}

Resources

A backup of all resources we were working with was made just before the finishing touches were done. No context will be given, though. If you can’t open 7z files, I’ve unpacked some of its files for this page.

Post-mortem

This year’s 4th challenge was harder than last year’s. I think there are three factors to this:

- The requirement was much more complex, having to reverse-engineer a blob of data we knew nothing about (well, I did know it contained the event flags, thanks to some VWF engine control character). The verification was also done by the server, so the most feedback we got was whether we succeeded or not at crafting our file. Last year only required REing smaller command packets which we also had a larger variety of. (Achievement getting, map requests, etc).

- Getting to the target code was more difficult, although not that much. Last year was basically as simple as setting a write breakpoint on the serial data byte, and you were a few stack entries away from it. This year required being more creative.

- Tougher techniques were used. Again, last year only used a simple XORing of the packets, whereas this year… well, this year had ROP chains, which I know people who eat those for breakfast, but I’m pretty sure some saw what was happening and just went “WTF is happening anymore”. And then you had to figure out it was a bytecode interpreter and what each opcode did, which the ROP basically obfuscated.

Then again, I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing; more people got perfect scores last year, and maybe the more difficult challenges increased the skill ceiling. I mean, consider that more than 30 people finished the first two challenges, and that around 20 finished the first three—finishing the third required a lot of creativity and effort already, so I applaud everyone who cracked it, even if they didn’t manage PK4.